I thought we’d head straight into battle. That we’d tear down whatever was holding Halven with the force we’d found in each other. But Isa and Veyn had other plans. They pulled us back into the Council Chambers—of all places—for training, after they took a few days to recuperate.

I didn’t like waiting, but if it meant getting Halven back, I’d learn whatever it took.

But I hated being in the Council Chambers.

Not because they were cold or austere or dripping with the weight of every law that had ever caged a fae. I hated them because he was there. Orivian. Sitting too near, breathing the same air like nothing had changed.

After the announcement that we’d be training for a few weeks, I told myself I wouldn’t go. I didn’t need Veyn’s lessons. I didn’t need diagrams or scrolls or maps drawn in chalk and charcoal. I could teach myself. I always had.

But I went anyway.

Because Halven was still frozen, and if learning to bind magic to nature was what it would take to get him back, then I would become a master of it before the rest of them learned how to hold a proper conduit.

I showed up late each night. I took my seat in the upper benches and made no effort to hide my disinterest in whatever Veyn was preaching at the front of the room. But I listened. And then, when we broke into practice, I worked alone.

The room, once cold and echoing with politics, took on a new pulse. It was alive now. Every hour we pushed harder, magic surging and colliding, not against each other, but something older, heavier, that pressed in at the edges.

It wasn’t just training. Veyn, still weak from what happened, told us we’d need to learn Binding magic, something elemental and deep-rooted. Not just casting, but anchoring. I had to figure out how that worked for my magic.

Metal was precise. Demanding. It did not suffer hesitation. So I forged my own rhythms. No shared intent. No partnered element to dilute what I already knew I could do.

The first few days, I worked in silence. I bent slivers of ore into strands and tried to anchor them to stone with nothing but breath and focus. It didn’t hold. Not for long. But I kept at it.

When Isa arrived on the third day of training, she didn’t even glance at me until the session was halfway through. Then, without preamble, she said, “Garnexis. Pair with Elio.”

I turned to protest, but her expression made it clear the conversation was over.

Elio raised a brow at me. “Lucky me.”

I rolled my eyes and stalked over to where he stood, earthy magic already humming under his fingertips.

To my surprise, he didn’t try to lead. He asked what I wanted to try, and then actually listened. We agreed to anchor a length of iron wire to a broken stone column near the rear wall using a pulse of my Metal and a ripple of his Earth. We set our intent aloud, and for once, I didn’t rush through it.

When it worked, I felt it settle deep in my chest. Not just success. Harmony.

I gave him a smile before I realized I had. And of course, he didn’t miss it.

“Careful,” he murmured. “That almost looked genuine.”

I snorted. “Try not to get used to it.”

Out of the corner of my eye, I caught movement.

Orivian. Of course. He just couldn’t let me go.

He was working with Lo near the far wall, and just as I looked over, he lost his focus. A silvery tendril of binding snapped with a sharp flicker and vanished into smoke. He didn’t look at me. But he did scowl—at Elio.

My stomach turned, but I shoved the reaction down where I kept all the things I didn’t want to feel.

We kept working, Elio and I, and soon our synchrony sharpened. Isa circled once, observing, and said, “You two share clear intent. An excellent pairing.”

It was not praise, at least I didn’t take it that way. But it was acknowledgment. And I would take it.

By the fifth day, I tried something new. I let go of the rigid structures I’d clung to and began syncing my breath with the metal’s shape.

My magic pulsed from the center of my chest in time with each inhale. I watched a thin arc of copper curl into the air like it knew what I needed. When I shaped it into a tiny bird and it hovered for half a second, responding not to command but to emotion, I almost didn’t breathe.

It worked.

I had found my rhythm.

And I didn’t need anyone to help me get there.

A short while later, a voice from behind the stone map caught my attention.

“It just doesn’t work,” Ardorion said, his tone edged with frustration. “Maybe fire doesn’t bind well with other elements because of where it comes from. Because of Ignis. The Fire God didn’t exactly get along with the others, considering his history. Maybe the other elements hold a grudge.”

I paused, just for a breath. It was rare to hear Ardorion admit doubt. Even rarer to hear him invoke the old gods as anything other than metaphor. Perhaps he was recalling how Ignis had destroyed and devasted Sygilla.

Veyn did not correct him. He simply said, “Fire takes on the qualities of its master. Like Ignis, fire consumes, transforms, and rages. But under the right conditions, it could also sustain.”

He folded his arms across his chest, voice softening just enough to reveal reverence. “Start by finding where fire lives in nature without destroying it.”

On the evening of Nonis 9th, Veyn called an early end to training.

“We will not train tomorrow,” he said. “Deveil’s Night is not a time for training. You are expected in the ceremonial field by twilight for the Mourning of the Mists. We walk through the mists so the wraiths pass us by on Deveil’s Night as we begin the Descent of the Veil.”

I gathered my things slowly, the echo of his words staying with me longer than they should have.

Deveil, the shortened form of The Descent of the Veil. I walked the mists for the first time last year, and I certainly didn’t see anyone who had crossed the veil of death already. It was all a jest, a merry tale to keep the dead alive somehow.

No one important to me had died anyway, so who would I expect to see or hear. It was just a waste of time. Time that we could spend training. Time to prepare to save Halven.

But I didn’t have a choice.

All Docilis had to attend the Mourning of the Mists, the ritual on Deveil’s Night, before the Descent of the Veil on the next day. Supposedly, this was when the veil thinned between the living and the dead. Something to do with two minor Fire Gods, Brihiva and Acratius, who had a son slain in battle.

A remembrance of lovers who dared to defy death. “The Descent of Brihiva and Acratius”—that was the story’s name. I read it once in the library. A tale of grief and resolve. Of two gods of war who tore through the veil to descend into the eight hells to rescue their son, Ashar, the God of Battle. However, Acratius had to stay behind while his wife and son returned to the living. A soul for a soul.

On the same day every year, the veil descended between the living and the dead.

I liked the story, even if I didn’t care for the ritual. The idea that someone could be forged by loss and still choose love. That held more truth than half the teachings at this academy.

Let the others pray to see spirits in the mist. I would take the story over the superstition.

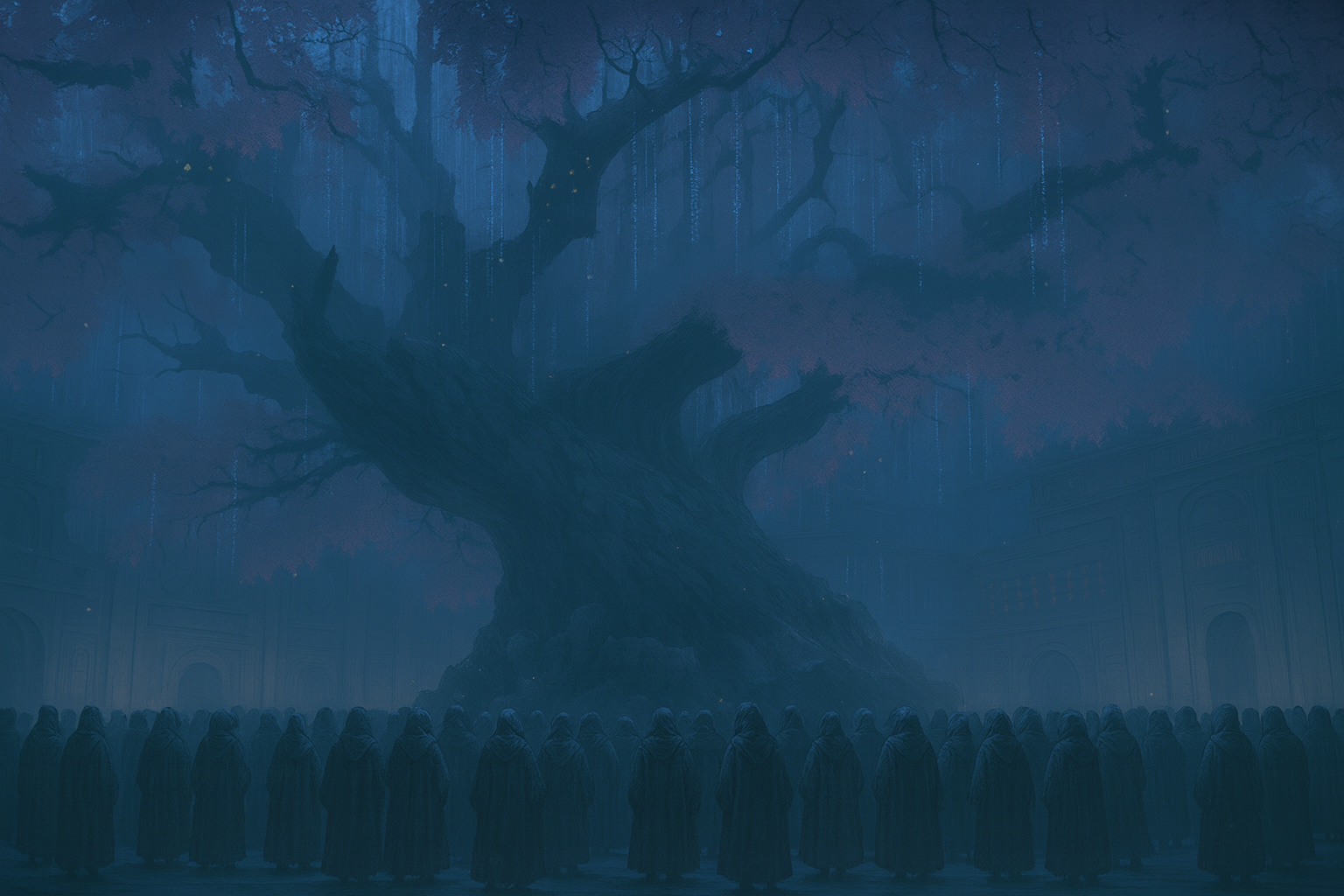

When twilight fell on Deveil’s Night, I joined the others at the edge of the ceremonial field, cloaked in gray and irritation. The air was wet. The mists had already begun to swell over the grass like breath from the belly of the mountain, curling thick and low, just as the myths said they would.

We stood in silence, faces veiled in pale silk, feet bare against the chill. A single flute carried a low tune somewhere beyond the stones, its melody haunting in a way that made some students bow their heads.

I did not.

The song was Ashar’s. It was said Ashar was the most accomplished flute player, who could move any audience to tears or laughter.

We moved forward in a line, one by one, across the slick grass and toward the ceremonial tree. Its bark looked darker than usual, water pooling in the hollows like old tears. Branches curled upward and out, stretching like skeletal arms trying to reach something they had long since lost.

I didn’t expect anything when I stepped into the mist. No vision. No revelation. Certainly no visitation.

Still, I kept my breath even. I walked like the rest of them, as if this mattered. As if it might matter.

Around me, I caught glimpses of others faltering in their steps, awe lighting their features beneath their veils. Some reached forward into the fog, hands trembling. Others closed their eyes like they could see someone I could not.

I kept walking.

One girl whispered something I could not hear. A boy let out a soft sob. None of it touched me. I had no dead waiting to speak with me. No voices from the other side. No long-lost parent or sibling to find in the shadows. No one I ever cared about had died, because that encompassed only one person. My mother.

Maybe the mists knew I didn’t believe in them. Maybe they passed me by on purpose.

I reached the base of the tree and knelt, not in reverence but out of respect for tradition. The wood beneath my fingers felt cold, rough. Real.

I stared at the mist and whispered nothing.

Because nothing was what I felt.

Still, I stayed a moment longer than I needed to. Just long enough to feel the smallest flickering hum of my fated bond beneath my skin. Orivian was close, but I didn’t want to see him.

As the flute played on and the mist curled tighter, I stood, pulled my cloak close, and walked back through the field.

I didn’t need this celebration.

I didn’t need anyone at all.